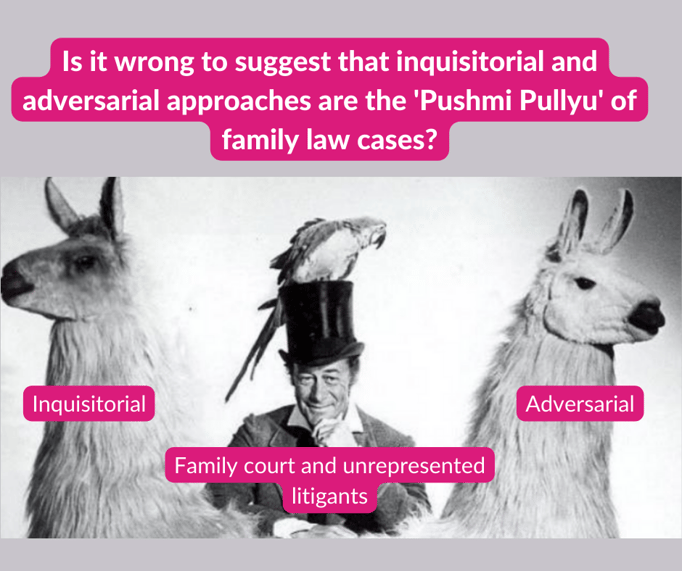

In his latest blog post written specially for family law professionals, John Bolch compares an adversarial versus inquisitorial system and the pros and cons when it comes to having no legal representation and litigants-in-person cast adrift in the legal system.

When the Government abolished legal aid for most private law family matters back in 2013 it obviously left huge numbers of litigants adrift, having to navigate an unfamiliar legal sea without the guidance of a lawyer.

Whereas before 2013 in only about 10% of cases were neither party represented, now the figure is nearly 40%. Correspondingly, before 2013 in nearly half of all cases both parties were represented, and now the figure has dropped to less than 20%.

The problem, of course, is that without legal representation, or at least advice, litigants in person will not know how best to present their case, often missing out entire lines of argument that would support the case, and pursuing others that would not.

This leads to a conundrum for a judge with a litigant-in-person appearing before them: how much assistance, if any, should they provide them?

The issue was neatly summarised by Mr Justice Mostyn in a recent High Court case.

Judicial encouragement

The case concerned an unrepresented wife’s appeal from a financial remedy order on divorce. Pointing out that the wife had curiously shown little interest in pursuing one of the grounds of the appeal, he said: “This raises the question of how much encouragement the court should give to a litigant-in-person to take the right points and to eschew the wrong ones.”

On the one hand, he said: “A judge will be criticised as having abandoned impartiality and independence, and of having descended into the arena, if he or she takes a point favouring one party’s case which that party has not raised”.

He continued: “It has been stated time and again, for example in [a Supreme Court case where] Lord Sumption stated: “Any advantage enjoyed by a litigant-in-person imposes a corresponding disadvantage on the other side, which may be significant if it affects the latter’s legal rights””.

On the other hand, however, Mr Justice Mostyn pointed out that: “in a financial remedy case the court exercises a quasi-inquisitorial function. It would be a dereliction of its inquisitorial duty if it allowed a case to be decided under procedural rules and customs which prevented a just decision being rendered on a particular set of facts because a litigant-in-person has, for whatever reason, chosen not to advance the relevant arguments applicable to those facts.”

Which raises the question: is it time for all family cases to be dealt with on an inquisitorial, rather than an adversarial, basis?

Time for an inquisitorial system?

Subject to what Mr Justice Mostyn said above, the family courts essentially deal with cases on an adversarial basis, the same as other civil courts. This means that each party is responsible for presenting their case, in an attempt to persuade the judge to make the order that they are seeking.

Crucially, it is not open to the judge to enquire beyond the facts and evidence that are presented by the opposing parties – he or she must make their decision on the basis of the evidence presented before them.

On the other hand in an inquisitorial system the role of the judge is to conduct an inquiry into the case. He or she is therefore not limited to hearing the evidence presented by the parties, but can also raise other matters that they consider may be relevant.

Many have suggested that an inquisitorial system is more appropriate for the resolution of family disputes.

For example, the President of the Family Division Sir Andrew McFarlane has indicated his support for a ‘more investigative’ approach to resolving parental disputes over arrangements for their children, and just last month he said that: “the adversarial nature of the court process is unlikely to have a healing impact on the participants.”

And of course an inquisitorial system will largely resolve the judicial conundrum of judges providing encouragement for litigants-in-person, at the expense of the other party.

For my part it has long seemed that an adversarial system, which obviously encourages conflict between the parties, is indeed not appropriate for the resolution of family disputes, where the outcome should be a response to the truth of the matter, rather than the skill with which a case is presented.

(Edit to add: for those of you not old enough to remember or know – the image is Rex Harrison playing Dr Dolittle from the 1967 musical film of the same name. Pictured is the Pushmepullyu, a half Llama/Unicorn hybrid, and contradictory in nature).

Video credit: Video by RODNAE Productions: https://www.pexels.com/video/a-woman-asking-question-during-conference-7647617/

John Bolch

John Bolch