In his latest exclusive for Cansford, Family Law blogger John Bolch bangs the drum for Family Drug and Alcohol Courts and also discusses a case held at Cardiff – pertinent to his article and the court closest to our laboratory….

Initial thoughts and setting the scene.

There is, I think, a public perception that the parents of children involved in care proceedings are beyond redemption, the makers of their own misfortune.

It is of course true that some parents of children taken into care fit this stereotype, but many do not.

I am talking in particular of parents caught up in the maelstrom of drug and alcohol abuse.

And I believe it is important that the public understand that many such parents can be helped, so that their children are not unnecessarily torn from their families.

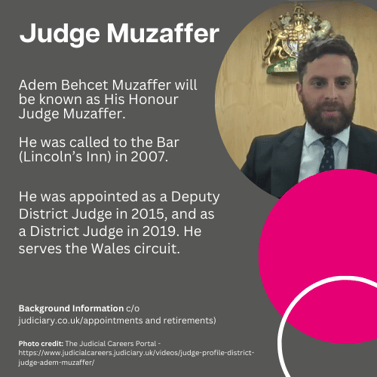

Why this is important can be seen from the recent judgment of His Honour Judge Muzaffer in the case Vale of Glamorgan Council v M & Anor.

Tragic case

The case was something of a tragedy, although it could have been so different.

It concerned care proceedings in relation to a little girl aged 8 months old, issued following concerns over her mother’s substance abuse.

I will let Judge Muzaffer set out the background (he refers to the mother as ‘M’):

“M is just 27 years old, but her life to date has been hard.

She came to the attention of the [Local Authority] when just 16 as her father had returned home drunk and assaulted her. It was around this time that M also became involved in an abusive relationship, and was introduced to alcohol, drugs, and criminality.

Substance misuse then remained the constant in M’s life as it descended into chaos. Between 2010 and 2023, she received 25 convictions for 50 offences, and in 2021 she received a 12 month custodial sentence for assault.

“At the time that M became pregnant, she was involved in two separate relationships … she experienced domestic violence at the hands of both men. Both were also known for their general criminality and substance abuse issues.”

We are then told that in the course of her pregnancy the mother continued to drink and use drugs, including benzodiazepines, cannabis, cocaine, methadone, and methamphetamine, and failed to engage with safeguarding professionals.

The Local Authority issued care proceedings after the child was born and, unsurprisingly, highlighted the mother as being potentially suitable for FDAC at Cardiff.

The mother embraced the help she received via FDAC, returning negative drug and alcohol tests, and engaging well with all professionals and the range of support on offer. Judge Muzaffer tells us that: “M visibly thrived in her work with the FDAC team. Her physical and emotional recovery from years of abuse was slow but evident fortnight to fortnight … Sober, M appeared to have a new lease of life.”

But it was not to last.

Unfortunately, the FDAC pilot at Cardiff concluded.

Whilst not necessarily linked to the closure, we are told that the mother began talking drugs again and her life again “spiralled into chaos”, with the inevitable result that care and placement orders were made.

Judicial regret

At the conclusion of his judgment Judge Muzaffer said this of FDAC:

“It is a matter of obvious regret that funding could not be secured for the Pilot to be extended, as this had clear implications for families and professionals involved in cases still before the court. The reality is that a talented, committed team have now been disbanded, and it will be a question of starting from scratch should the go-ahead ever be given.

“The Pilot has been the subject of a thorough and detailed evaluation report. Once finalised and published, I hope it is given the attention and scrutiny that it deserves by both those holding the purse strings and the wider public. There is now a wealth of positive evidence supporting the use of FDAC as an alternative form of care proceedings in the Family Court.”

He went on: “Cases such as this demonstrate just how hard it is for parents to escape entrenched harmful patterns of behaviour. Although M was tasked with the considerable challenge of breaking a cycle that had started in her early teens, she was always treated as an individual and given a real chance to engage with targeted treatment and support. Had this been of benefit to M, it would have been of benefit to [the child]. That must surely be the more humane and constructive way to conduct care proceedings of this type, even if the outcome here was not the one hoped for.”

So hopefully the Cardiff FDAC can be re-established if, as Judge Muzaffer says, its evaluation report is given the attention and scrutiny that it deserves by both those holding the purse strings and the wider public.

In other words, it requires money and public support.

Money can always be found. After all, the government has just announced that, after years of court shortages, it has miraculously found 25 courtrooms and 150 judges who could provide over 5000 sitting days to deal with cases arising from its immoral, inhumane, and utterly shameful Rwanda policy (otherwise known as its ‘last desperate attempt to attract enough votes to avoid electoral oblivion’ policy).

No, money isn’t the issue. The issue is finding the will to establish FDACs across the country, which will only come when sufficient numbers of people support the idea.

And that will only come if sufficient numbers of people are educated about FDACs and their benefits.

We have already recently lost FDACs in Somerset and Kent due to lack of funding, and now there are none at all in Wales. This is a tragedy – all parents and children involved in these cases deserve the help that FDACs can bring them.

It is essential that there be greater public awareness of FDACs, and the excellent work that they do. Hopefully this post will, in its very small way, increase that awareness, and that ultimately we will have a network of FDACs covering all of England and Wales.

John Bolch

John Bolch